"The eightfold path is the best of ways."

From the "Dhammapada" and its chapter entitled, "The Way"

(TDP, p. 75)

One of the most interesting things about studying with Ajari Tanaka is his deep appreciation and emphasis on the teachings of Shakamuni Buddha. That might seem like a ridiculous way to characterize ones Dharma teacher, but it's true. In this respect Ajari Tanaka is an intriguing combination. As one of Japan's only Shingon masters actively teaching Western students, he's worked tirelessly to share a mostly unknown Tantric system of practice as well as help us appreciate the profundity of Kobo Daishi Kukai's teaching and contribution to Japanese thought, history and culture. But, all the while he keeps lecturing on the teachings of Buddhism's original founder, especially those that are earliest and most fundamental.

One of the most interesting things about studying with Ajari Tanaka is his deep appreciation and emphasis on the teachings of Shakamuni Buddha. That might seem like a ridiculous way to characterize ones Dharma teacher, but it's true. In this respect Ajari Tanaka is an intriguing combination. As one of Japan's only Shingon masters actively teaching Western students, he's worked tirelessly to share a mostly unknown Tantric system of practice as well as help us appreciate the profundity of Kobo Daishi Kukai's teaching and contribution to Japanese thought, history and culture. But, all the while he keeps lecturing on the teachings of Buddhism's original founder, especially those that are earliest and most fundamental. As a young man Ajari Tanaka spent five years in India with the express purpose of connecting with what the historical Buddha taught. Over the course of his teaching in US, Canada and Europe he has often given Dharma talks inspired exclusively by Gotama Buddha. In Japan he regularly devotes entire semesters at Waseda University to the Dhammapada or the Sutta Nipata. Here in Vermont he has given an untold number of Dharma talks in our retreats on the life of the Buddha. Many of his North American students have heard him take a big in-breath, then say, "Shakamuni Buddha" and talk for the next hour.

So Ajari Tanaka has given us ample encouragement to explore and build our understanding of these original Dharma teaching. They represent an important part and perhaps an under-examined part of our training. Ajari Tanaka has demonstrated over time and through his consistent emphasis that it is important to study these dharmic fundamentals. Without coming out and giving us homework, he is suggesting in an indirect way that we make a genuine effort to bring Shakamuni's Dharma into our Mikkyo practice.

So armed with that inspiration, this post will attempt explore some of the basics of the Noble Eightfold Path. Not a deep dive into each element, but a start. First a look at the context and characteristics of the path and then practice of meditation within it. Ajari Tanaka has continually stressed that personal daily practice is first and foremost, so we'll take that as a guide in beginning to appreciate the Noble Eightfold Path.

(Those interested in very comprehensive treatment of the Noble Eightfold Path, please refer to the books listed in this post's bibliography.)

The Noble Eightfold Path, or the "Ariya Atthangika Magga" (WBT, p. 45) is counted among Shakamuni Buddha's earliest teachings. It is the fourth of the Four Noble Truths. Recognizing the universality of suffering (the First Noble Truth) as the principle human problem, the Buddha gave the Noble EightFold Path as its cure. It is the way he posited that by our own effort we could each bring about the end of suffering.

The Buddha referred to the Noble Eightfold Path specifically as:

"...the path leading to the cessation of suffering..."

(FDB, p. 19).

Understood in this most basic context, the Noble Eightfold Path offers not only practical, but almost elemental value to our lives.

Master Kukai locates the Eightfold Path in our study and practice of Shingon in his "Precious Key to the Secret Treasury". From the section regarding the Fourth Level of Mind, Master Kukai states the following:

"The great Buddha, the World Honored One, therefore preached the Goat Vehicle in order to save the people from the extreme suffering of falling into the Three Evil Paths and to release them from the karmic fetters of the Eight Sufferings. His teaching is to promote the study of the Tripitika and to observe widely the Four Noble Truths."

(KMW, p. 176)Here we can see Kobo Daishi Kukai identifying the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path as the Fourth Level of Mind. Therefore indispensable in our Shingon Path as each level of Mind must be reached, learned, practiced and internalized if the fruition of the Shingon teachings are to be realized.

Turning now to an English language version of the Buddha's first teaching, very early in the translation we find the following:

"...the Tathagata has realized the Middle Path. It produces vision, it produces knowledge, it leads to calm, to higher knowledge, to enlightenment, to nibbana."

(FDB, p. 17)Here the Buddha begins to describe what he discovered in his meditation, as well as the result of that discovery. But what is the Middle Path precisely? First, the Buddha teaches that the path is characterized by its navigation between two extremes.

"O bikkhus, one who has gone forth from worldly life should not indulge in these two extremes. What are the two? There is indulgence in desirable sense objects, which is low, vulgar, worldly, ignoble, unworthy and unprofitable and there is devotion to self-mortification, which is painful, unworthy and unprofitable."

(FDB, p. 17)Even though we may have not "gone forth from worldly life", avoiding what is "unworthy and unprofitable" sounds like pretty good advice. Even in the context of lay life, it just makes sense that being continually too easy on oneself or incessantly hard is problematic. Vacillating between the two seems even worse. In the context of trying to develop a genuine meditative discipline within the demands of our daily life this kind of self criticism and/or indulgence can undermine our efforts.

Its safe to say that modern, lay life is full of creature comforts, entertainments and diversions. Today's world makes the pursuit of the enjoyable as easy as its ever been. In contrast it is equally tempting to endlessly scold ourselves when trying to develop a meditative discipline. It is far too easy to demonize the inevitable lapses in practice that happen or to get overly focused on (and judge negatively) the distracted nature of the mind while sitting in meditation.

So the simple necessity of taking a balanced approach to our lives and practice is established by the Buddha straight away. Of course the Buddha's definition of the extremes may be a bit bigger than our own. He lived a royal life as a young man and then was a hardcore ascetic. Our version of the extremes may be more modest. But they still exist - pushing too hard or not pushing enough all happens continually.

What seems most important is to recognize that this emphasis on balance is the context the Buddha set for the other teachings he shared.

The Buddha goes on, and as is characteristic of his teaching style, he gives a detailed list:

"And what is that Middle Path, O bhikkus, that the Tathagata has realized? It is simply the Noble Eightfold Path, namely: Right understanding, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right awareness, and right concentration. This is the Noble Eightfold Path realized by the Tathagata. It produces vision, it produces knowledge, it leads to calm, to higher knowledge, to enlightenment, to nibbana."

(FDB, p. 17)Just running down that list, without knowing anything of the specifics of what the Buddha precisely meant by understanding, thought, speech, action or all the rest, the Eightfold Path appears as a comprehensive, common sense way we might approach life.

No matter what kind of life we lead, there are a lot of moving parts. Its not a stretch to imagine that it might be helpful if we not only identified and paid attention to those differing aspects of our life, but also tried to make some improvement. Attending closely to our thinking, our speech, what we do, how we earn a living, what kind of energy we bring to our lives, all seems almost blandly practical. But at the same time, simply just plain smart.

But before we dig in and try to understand any specific dimension of this path a little bit more, it's important define the term "right." Each aspect of the path is prefaced with the term and so "right" must carry some significance worth defining.

In his work entitled, "The Myth of Freedom" in a section devoted to the Noble Eightfold Path, Chogyam Trungpa gives this comment:

"...we first must understand what the Buddha meant by "right." He did not mean to say right as opposed to wrong at all. He said "right" meaning "what is," being right without the concept of what is right."

(MOF, p. 95)

So the Buddha's "right" is not a relative term. Trunpa suggests the use of "right" in this context has more to do with the reality of our understanding, our thoughts and actions and the rest.

Trungpa further elaborates on his meaning, providing these additional specifics:

"Right" translates the Sanskrit "samyak", which means "complete." Completeness needs no relative help, no support through comparison; it is self-sufficient. Samyak means seeing life as it is without crutches, straightforwardly.

(MOF, p. 95)Knowing now that right is "samyak" or "complete" we can restate the Eightfold Path - Complete Understanding, Complete Thought, Complete Livelihood, Complete Effort, Complete Meditation, etc. This results in a different feeling for the elements of the path. It give a sense of perfecting these dimensions of life. Developing them to the point that our experience is complete - nothing more need be added and perhaps equally important, nothing remains to be removed.

Armed with a basic notion of "samyak", we can turn our attention to another useful English language resource. "What the Buddha Taught" by Walpola Rahula dissects the Eightfold Path into what Master Kukai calls the "Three Items of Mastery". Which are:

"Observance of the precepts, practice of meditation and obtaining wisdom"

(KMW, p. 172).The "Three Items of Mastery" are commonly referred to by the Sanskrit terms Sila, Samadhi and Prajna. In his note on the three, Prof. Hakeda states that they are:

"...the most comprehensive summary of the way of life and practice, and of the goal of Buddhists."

(KMW, p. 172)Professor Hakeda was a Shingon Acharya and life long scholar practitioner who lived for many years in the States. He was an accomplished translator and a respected professor at Columbia University as well as a friend of Ajari Tanaka's. When he states that the Three Items of Mastery, which are synonymous with the the Eightfold Path, are the "goal of Buddhists" he gives a clear indication of the universal applicability of Shakamuni's original conception of the path. Especially in the context of Mikkyo practice and study.

Returning to Rahula, here is how the Noble Eightfold Path is divided into the Three Items of Mastery:

Sila, or Discipline

- Right Speech

- Right Action

- Right Livelihood

(WBT, p. 46 - 47)

Samadhi, or Meditation

- Right Effort

- Right Mindfulness

- Right Concentration

(WBT, p. 47 - 48)

Prajna, or Insight/Knowledge/Wisdom

- Right Thought

- Right Understanding

(WBT, p. 49)

Regarding the deep and broad nature of these teachings, Rahula states the following:

And because we don't have forty-five years for this post we will not attempt to dive into all eight aspects of Shakamuni's path. As mentioned earlier, if one is so inspired, please refer to the resources listed in the bibliography below (I hope you won't be disappointed).

But what we will tackle is that element of the path that is most closely aligned with Ajari Tanaka's approach to teaching and training students. This directs us towards meditation, the practice of samadhi.

In all the years Ajari Tanaka has taught in the West, he has always kept an unrelenting focus on practice. Whether it be silent meditations, endless recitations, finger tangling mudra, visualizations or sadhana, his continuous emphasis indicated a confidence in the power of practice to unlock the totality of the path. Once a student gained an understanding of themselves though the natural inquiry that occurs in meditation (whatever the method), the other dimensions of the path - bringing ordered discipline to our lives or experiencing broader understanding, penetrating insights or empathy for others - all that would naturally arise as an outcome of that strong, consistent practice.

Practically the whole teaching of the Buddha, to which he devoted himself during 45 years, deals in some way or other with this Path. He explained it in different ways and in different words to different people, according to the stage of their development and their capacity to understand and follow him. But the essence of the many thousand discourses scattered in the Buddhist Scriptures is found in the Noble Eightfold Path.

(WBT, p. 45 - 46)

Rahula, in the strongest of terms asserts the utter centrality of the Noble Eightfold Path within all of Shakamuni Buddha's teaching.

But what we will tackle is that element of the path that is most closely aligned with Ajari Tanaka's approach to teaching and training students. This directs us towards meditation, the practice of samadhi.

In all the years Ajari Tanaka has taught in the West, he has always kept an unrelenting focus on practice. Whether it be silent meditations, endless recitations, finger tangling mudra, visualizations or sadhana, his continuous emphasis indicated a confidence in the power of practice to unlock the totality of the path. Once a student gained an understanding of themselves though the natural inquiry that occurs in meditation (whatever the method), the other dimensions of the path - bringing ordered discipline to our lives or experiencing broader understanding, penetrating insights or empathy for others - all that would naturally arise as an outcome of that strong, consistent practice.

And within the three dimensions of Samadhi, we will further constrain our exploration to Right Mindfulness.

In Pali, Right Mindfulness is "samma sati" (WBT, p. 45). In a series of lectures given at Karma Triyana Dharmachakra (the North American Seat of His Holiness the Karmapa) Dzogchen Ponlop gave the Sanskrit for "sati" as "smirti." During these lectures, Ponlop defined smirti as "recollection" or "memory". But not "recollection" in the sense of remembering something from the past, but rather to recollect or recognize the present moment (FFM, t. #1). So mindfulness in this context is the concerted effort to first recognize, then come back to and eventually abide in the present moment. And samyak smirti, would be its fruition, the complete re-collection within this present moment.

This echoes themes Ajari Tanaka has spoken to often. Many of us have heard him say we must "wake up" to "this present moment, right now."

Master Kukai's poetry perhaps captures it best. In the Iroha we find:

Turning back to Rahula, he expands the specific meaning and dimensions of Right Mindfulness:

Known commonly as the "Four Foundations of Mindfulness" Rahula locates this practice among the Buddha's teachings as follows:

In addition Rahula identifies a core practice associated with the development of Right Mindfulness:

Regarding meditations Ajari Tanaka taught Aji-kan first and emphasized it strenuously as one of our core practices. During our two hour Sunday morning practice sessions held at Vermont's original Mandala Buddhist Center, many started with forty-five minutes of Ajai-kan. After entering the dojo, doing our prostrations, Ajari would say, "face the wall". This meant to gaze at the Aji image and practice this essential method until the gong sounded.

Regarding meditations Ajari Tanaka taught Aji-kan first and emphasized it strenuously as one of our core practices. During our two hour Sunday morning practice sessions held at Vermont's original Mandala Buddhist Center, many started with forty-five minutes of Ajai-kan. After entering the dojo, doing our prostrations, Ajari would say, "face the wall". This meant to gaze at the Aji image and practice this essential method until the gong sounded.

Years later, Ajari Tanaka taught "Gaccharin-kan", or full moon meditation. In subsequent years Ajari has said that this meditation is very ancient and predates Shingon's arrival in Japan.

And again, years later, Ajari introduced "Susoku-kan" or "breath counting meditation." This method, that utilizes counting the exhalations has much in common with Zazen, central to Japan's Zen traditions and the Shamatha practices common in the Tibetan traditions. But more importantly it was directly connected to Shakamuni's teaching on the Four Foundations.

This passage is from the Anapanasati Sutta. Here the Buddha identifies the simple method of bringing awareness to our breathing as the practice that opens the door to understanding our minds and ultimately liberating our minds. The method Susoku-kan that Ajari Tanaka taught us late in our training, is that critical first step to our enlightenment.

Each year we have a retreat, usually near the end of Ajari's visit. It is our most important event of the year. It is never a large event. Usually not more than twenty people. But to our small sangha this is big stuff. Local longtime sangha folks, hardworking students who live outside Vermont - New York, Philadelphia, Maine, Ottowa, Toronto - and of course new friends and students, they all descend on Vermont to practice together and spend time with our teacher.

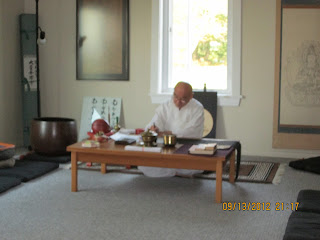

During his Vermont visit in September 2015, due to a quirk of the schedule we were able to have an early practice intensive with Ajari Tanaka. Compared to the main retreat that year, this opening weekend was sparsely attended. Just five of us joined Ajari at our New Haven (VT) dojo.

As is customary, we certainly practiced many of our core methods - prostrations, Sanmitsu-kan, Goshinbo, Enmei Juku Kannon Gyo, Hannya Shingyo, dharani and mantra - all the recitation and attending mudra that populate our group practice style. But what set this event apart from all others was our meditation. During this retreat Ajari Tanaka had us practice just simple sitting, Susoku-kan. In this event we just sat and paid attention to our breathing more than we ever had before.

In between simply sitting, Ajari talked quietly but passionately about the primacy of Anapanasati Yoga, following one's breathing. He encouraged its strenuous practice. The way he shared his thoughts and how he lead us in practice fostered meditations that were particularly deep and rich. This intensive was a clear example of Ajari's teaching genius. Those of us who attended remember the palpable experience of stillness and quiet.

Ajari Tanaka started teaching Western students in 1978. The years since are marked by an unrelenting effort to transmit Shingon to the students that gathered. First he vigorously taught a practice curriculum of esoteric fundamentals. Brick by brick he built our practice foundation. Then he worked to produce a corpus of Shido Kegyo texts that represent the proper practice of these core sadhanas in accord with his lineage. The work continued, training his senior students in the practice of these sadhanas. And most recently, he has charged those senior students with welcoming and supporting new students.

So after thirty-seven years of teaching and training students in a rare, almost unknown Tantric tradition, he returned for two days to Dharma's most basic meditation. Those of us who have been with Ajari Tanaka for a long time, this event was nothing short of remarkable. It felt like the completion of a very long cycle.

This echoes themes Ajari Tanaka has spoken to often. Many of us have heard him say we must "wake up" to "this present moment, right now."

Master Kukai's poetry perhaps captures it best. In the Iroha we find:

"Today cross over the deep mountains of life's illusion and there will be no more shallow dreaming..."

(SCE, p. 213)Turning back to Rahula, he expands the specific meaning and dimensions of Right Mindfulness:

"Right Mindfulness (or Attentiveness) is to be diligently aware, mindful and attentive with regard to (1) the activities of the body (kaya), (2) sensations or feelings (vedana), (3) the activities of the mind (citta) and (4) ideas, thoughts, conceptions and things (dhamma)."

(WBT, p. 48)Known commonly as the "Four Foundations of Mindfulness" Rahula locates this practice among the Buddha's teachings as follows:

"These four forms of mental culture or meditation are treated in detail in the Satipatthana-sutta..."

(WBT, p. 48)In addition Rahula identifies a core practice associated with the development of Right Mindfulness:

"The practice of concentration on breathing (anapanasati) is one of the well-known exercises, connected with the body, for mental development."

(WBT, p. 48) Regarding meditations Ajari Tanaka taught Aji-kan first and emphasized it strenuously as one of our core practices. During our two hour Sunday morning practice sessions held at Vermont's original Mandala Buddhist Center, many started with forty-five minutes of Ajai-kan. After entering the dojo, doing our prostrations, Ajari would say, "face the wall". This meant to gaze at the Aji image and practice this essential method until the gong sounded.

Regarding meditations Ajari Tanaka taught Aji-kan first and emphasized it strenuously as one of our core practices. During our two hour Sunday morning practice sessions held at Vermont's original Mandala Buddhist Center, many started with forty-five minutes of Ajai-kan. After entering the dojo, doing our prostrations, Ajari would say, "face the wall". This meant to gaze at the Aji image and practice this essential method until the gong sounded.Years later, Ajari Tanaka taught "Gaccharin-kan", or full moon meditation. In subsequent years Ajari has said that this meditation is very ancient and predates Shingon's arrival in Japan.

And again, years later, Ajari introduced "Susoku-kan" or "breath counting meditation." This method, that utilizes counting the exhalations has much in common with Zazen, central to Japan's Zen traditions and the Shamatha practices common in the Tibetan traditions. But more importantly it was directly connected to Shakamuni's teaching on the Four Foundations.

"O bhikkus, the method of being fully aware of breathing, if developed and practiced continuously, will have great rewards and bring great advantages. It will lead to success in practicing the Four Establishments of Mindfulness. If the method of the Four Establishments of Mindfulness is developed and practiced continuously, it will lead to success in the practice of the Seven Factors of Awakening. The Seven Factors of Awakening, if developed and practiced continuously, will give rise to understanding and liberation of the mind."

(AH, p. 10)This passage is from the Anapanasati Sutta. Here the Buddha identifies the simple method of bringing awareness to our breathing as the practice that opens the door to understanding our minds and ultimately liberating our minds. The method Susoku-kan that Ajari Tanaka taught us late in our training, is that critical first step to our enlightenment.

Each year we have a retreat, usually near the end of Ajari's visit. It is our most important event of the year. It is never a large event. Usually not more than twenty people. But to our small sangha this is big stuff. Local longtime sangha folks, hardworking students who live outside Vermont - New York, Philadelphia, Maine, Ottowa, Toronto - and of course new friends and students, they all descend on Vermont to practice together and spend time with our teacher.

During his Vermont visit in September 2015, due to a quirk of the schedule we were able to have an early practice intensive with Ajari Tanaka. Compared to the main retreat that year, this opening weekend was sparsely attended. Just five of us joined Ajari at our New Haven (VT) dojo.

As is customary, we certainly practiced many of our core methods - prostrations, Sanmitsu-kan, Goshinbo, Enmei Juku Kannon Gyo, Hannya Shingyo, dharani and mantra - all the recitation and attending mudra that populate our group practice style. But what set this event apart from all others was our meditation. During this retreat Ajari Tanaka had us practice just simple sitting, Susoku-kan. In this event we just sat and paid attention to our breathing more than we ever had before.

In between simply sitting, Ajari talked quietly but passionately about the primacy of Anapanasati Yoga, following one's breathing. He encouraged its strenuous practice. The way he shared his thoughts and how he lead us in practice fostered meditations that were particularly deep and rich. This intensive was a clear example of Ajari's teaching genius. Those of us who attended remember the palpable experience of stillness and quiet.

Ajari Tanaka started teaching Western students in 1978. The years since are marked by an unrelenting effort to transmit Shingon to the students that gathered. First he vigorously taught a practice curriculum of esoteric fundamentals. Brick by brick he built our practice foundation. Then he worked to produce a corpus of Shido Kegyo texts that represent the proper practice of these core sadhanas in accord with his lineage. The work continued, training his senior students in the practice of these sadhanas. And most recently, he has charged those senior students with welcoming and supporting new students.

So after thirty-seven years of teaching and training students in a rare, almost unknown Tantric tradition, he returned for two days to Dharma's most basic meditation. Those of us who have been with Ajari Tanaka for a long time, this event was nothing short of remarkable. It felt like the completion of a very long cycle.

Maybe it was the quiet and still fruition of all those years of wondrous effort.

__________________________________________________________________

Bibliography

The Dhammapada, Balangoda Ananda Maitreya, Parallax Press, 1995, abbreviated in notation as (TDP, p. XX)

The First Discourse of the Buddha, Dr. Rewata Dhamma, Wisdom Publications, 1997, abbreviated in notations as (FDB, p. XX)

What the Buddha Taught, Walpola Rahula, Grove Press, 1959, abbreviated in notations as (WBT, p. XX)

Kukai: Major Works, Yosito S. Hakeda, Columbia University Press, 1972, abbreviated in notations as (KMW, p. XX)

The Myth of Freedom, Chogyam Trungpa, Shambhala, 1976, abbreviated in notations as (MOF, p. XX)

Exploring the Four Foundations of Mindfullness, Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche, translated by Lama Yeshe Gyamtso, at Karma Triyana Dharmachakra, Woodstock NY, April 4 - 6, 2014, recorded by Dharma Echoes abbreviated in notes as (FFM, t. X)

Sacred Calligraphy of the East, Third Edition, John Stevens, Echo Point Books & Media, 2013, abbreviated in notes as (SCE, p. XX)

Awakening of the Heart, Thich Nhat Hanh, Parallax Press, 2012, abbreviated in notes as (AH, p. XX)